If you’ve ever lived in fear of being hacked and your funds siphoned by a malicious actor, leading blockchain security firm Certora attempted to alleviate those fears on Thursday, February 12, by means of a livestream titled “How DeFi Hacks Have Changed in the Last 5 Years and What This Means for Protocols.”

Certora CEO Seth Hallem joined Ofek Ray Orlev, a senior security researcher and team lead at the company, to analyze how modern attacks differ from earlier DeFi exploits and what protocol teams should do in response.

Seth joined Certora eight months ago after building a career in static analysis, software quality, and cybersecurity. He now applies that experience to Web3 and DeFi. Ofek brings twelve years of vulnerability research experience across offensive and defensive domains. Before entering the DeFi space two years ago, he led red teaming and penetration testing efforts at Intel, where he developed both offensive and defensive tools for embedded systems.

Rather than revisiting well-known hacks, the discussion focused on two recent and sophisticated attacks. The first, CPIMP, stands for Clandestine Proxy In The Middle of Proxy. The second, GlassWorm, represents the first crypto-targeted, self-propagating worm to attack the NPM and OpenVSX supply chain. Together, these attacks illustrate how DeFi security has shifted from obvious bugs to systemic, patient, and multi-layered campaigns.

Clandestine Proxy In The Middle of Proxy (CPIMP) Attack

The CPIMP attack exploits proxy initialization patterns in smart contracts. At its core, the attack hijacks the initialization phase of a proxy contract. If an attacker front-runs the first initialization call, the attacker can initialize the proxy with a malicious implementation.

What makes CPIMP particularly notable is not just its initial foothold but also the persistence and stealth that follow. The malicious proxy imitates the intended implementation, so all tests and normal interactions continue to pass. Developers and users see no obvious malfunction. The attacker inserts a clandestine proxy between the legitimate proxy and its intended logic, which allows the attacker to intercept and manipulate calls without immediate detection.

The malicious actors also engineered persistence across upgrades. When developers upgrade the proxy to add features, the malicious layer reinjects its code into the new implementation. Once infected, every subsequent upgrade flows through the attacker’s pipeline. This design enables long-term control rather than a quick smash-and-grab exploit.

The attackers even exploited a vulnerability in Etherscan that allowed them to spoof the displayed implementation address by populating an outdated storage slot. External observers relying on block explorers would see the wrong implementation, further obscuring detection.

Seth and Ofek compared this approach to a rug pull but emphasized a different time horizon. A traditional rug pull often drains funds quickly. CPIMP appears designed to wait until a protocol grows large enough to justify activation. The attacker can treat the compromised system as a dormant asset that matures over time. That patience suggests a campaign mindset rather than opportunistic exploitation.

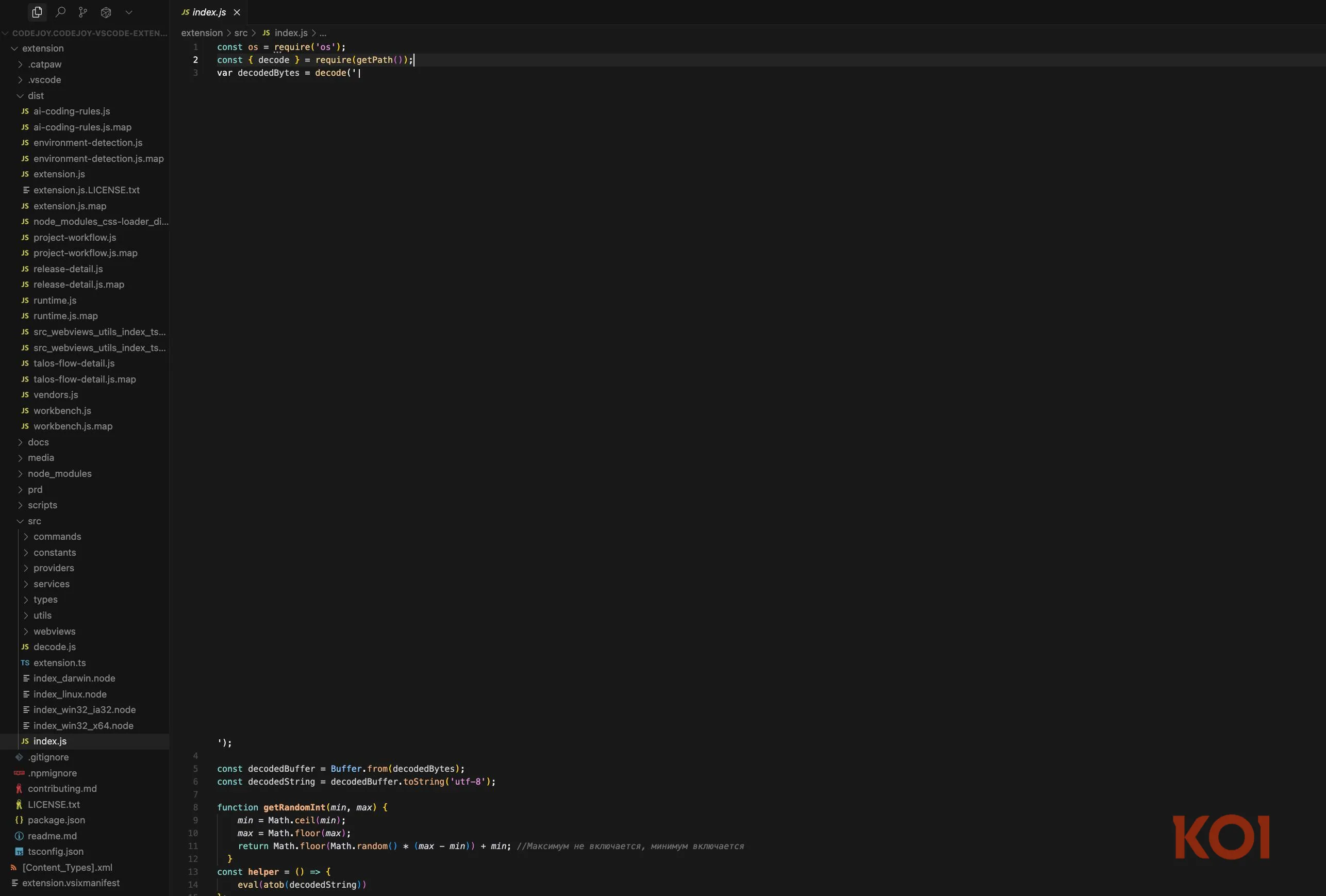

GlassWorm Attack: Extracting Private Keys From 50 Wallet Extensions

GlassWorm shifts the battlefield from onchain logic to the development supply chain. Attackers introduced a malicious VS Code extension that infected developers’ machines. Once installed, the extension extracted private keys from approximately fifty wallet extensions. It also searched for GitHub credentials and determined whether the infected developer maintained other VS Code extensions.

If the developer published an extension, the worm injected malicious code into that extension before distribution. This propagation mechanism transformed the malware into a true worm. Each newly infected extension spreads the payload further, amplifying its reach across the ecosystem.

Take a second to understand that information. You’re a developer. Your machine gets infected. You probably get drained of your funds. Any extensions you develop get infected, and anyone who downloads them also gets their machine infected, and so on.

The “glass” label refers to the use of unprintable characters to hide malicious code. The payload appeared as blank lines or whitespace in editors. Traditional static analysis tools failed to flag the code before researchers identified the attack.

GlassWorm combined known techniques with new innovations. It reused established supply chain compromise strategies and private key extraction methods. However, it introduced a novel command-and-control mechanism by leveraging the Solana blockchain. The worm read encrypted instructions embedded in transaction memo fields. Because attackers signed those transactions with their own wallet, infected machines could verify and execute new instructions without relying on a traditional server.

This onchain command-and-control design made takedown efforts far more difficult. Law enforcement or security teams could not simply seize a centralized server. The attackers also used Google Calendar event subjects as a backup communication channel. These layers created resilience and flexibility that security researchers rarely observe in earlier Web2 worms.

The worm also installed a hidden VNC client and configured a SOCKS proxy on infected machines. Those capabilities indicate that the attackers sought more than wallet drains. They aimed to gain broad access to victims’ systems. The attack blurred the line between Web2 and Web3 and demonstrated that DeFi security no longer stops at smart contracts.

What Can You Do To Protect Yourself?

Both speakers stressed that developers should not adopt a nihilistic mindset. Perfect security does not exist, but practical improvements significantly reduce risk.

Ofek advised teams to scrutinize their toolchains, limit unnecessary extensions, and keep dependencies up to date. He urged developers to really understand how their deployment processes actually execute.

He also recommended post-deployment verification. Teams should inspect onchain storage slots directly rather than rely solely on block explorers. They should confirm that no unexpected delegatecalls or initialization steps occurred.

Seth emphasized architectural thinking. He stated, “the idea that a browser extension is a safe place to decrypt a private key and sign transactions that move money is a flawed concept built from the wrong threat model.” He argued that browser extensions run in highly dynamic environments and should not handle high-value cryptographic operations. Hardware security modules and isolated signing environments offer stronger guarantees.

Mert Mumtaz, CEO of Helius Labs, echoed that sentiment in a public post, writing that the idea that wallets are Chrome extensions represents one of the industry’s most questionable UX decisions.

Both perspectives highlight the need to rethink wallet security assumptions as capital inflows increase.

What Should You Watch Out For In 2026?

Looking ahead to 2026, both speakers expect increased institutional participation in Web3. As governments and large financial institutions evaluate deeper involvement, protocols will face stricter due diligence and compliance requirements. Documentation, formal verification, standardized procedures, and continuous security partnerships will likely become baseline expectations.

On the offensive side, attackers will continue blending Web2 and Web3 techniques. As smart contract quality improves and audits become more common, attackers will target social engineering, private key exfiltration, frontends, governance processes, and supply chains. Seth compared this shift to the rise of ransomware in Web2 after organizations hardened exposed services.

Protocols should expect attackers to behave like businesses. Some campaigns will pursue transactional gains such as phishing and wallet drains. Others will pursue strategic opportunities that target systemic weaknesses in trillion-dollar infrastructures.

Final Reflections

The livestream highlighted a clear shift in DeFi security. Early exploits often relied on obvious coding mistakes. Modern attacks operate with patience, persistence, and cross-domain sophistication. CPIMP demonstrated how attackers can hide inside proxy architectures and wait for value to accumulate. GlassWorm showed how supply chain compromises and onchain command-and-control can extend beyond smart contracts into developer environments.

Protocols cannot predict every future technique. They can, however, raise the cost of attack through disciplined architecture, careful deployment, minimized threat surfaces, and continuous verification. As capital and regulatory scrutiny increase, security will move from a point-in-time audit to an ongoing operational requirement.

Read More on SolanaFloor

Developers on Solana Increase Almost 10X Since 2020 as Network Welcomes a Record 3830 New Devs in 2025

Solana Perps Scene Snubbed Once Again As Trojan Terminal Integrates Elsewhere

Can Digital Asset Treasuries Survive the Crash?